-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ana Bozas, Kelly J Beumer, Jonathan K Trautman, Dana Carroll, Genetic Analysis of Zinc-Finger Nuclease-Induced Gene Targeting in Drosophila, Genetics, Volume 182, Issue 3, 1 July 2009, Pages 641–651, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.101329

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Using zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) to cleave the chromosomal target, we have achieved high frequencies of gene targeting in the Drosophila germline. Both local mutagenesis through nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) and gene replacement via homologous recombination (HR) are stimulated by target cleavage. In this study we investigated the mechanisms that underlie these processes, using materials for the rosy (ry) locus. The frequency of HR dropped significantly in flies homozygous for mutations in spnA (Rad51) or okr (Rad54), two components of the invasion-mediated synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) pathway. When single-strand annealing (SSA) was also blocked by the use of a circular donor DNA, HR was completely abolished. This indicates that the majority of HR proceeds via SDSA, with a minority mediated by SSA. In flies deficient in lig4 (DNA ligase IV), a component of the major NHEJ pathway, the proportion of HR products rose significantly. This indicates that most NHEJ products are produced in a lig4-dependent process. When both spnA and lig4 were mutated and a circular donor was provided, the frequency of ry mutations was still high and no HR products were recovered. The local mutations produced in these circumstances must have arisen through an alternative, lig4-independent end-joining mechanism. These results show what repair pathways operate on double-strand breaks in this gene targeting system. They also demonstrate that the outcome can be biased toward gene replacement by disabling the major NHEJ pathway and toward simple mutagenesis by interfering with the major HR process.

EXPERIMENTAL gene targeting relies on cellular DNA repair activities. When a donor DNA carrying the desired sequence modifications is introduced into cells or organisms, successful gene replacement depends on cellular capabilities for homologous recombination (HR).

We have developed a very efficient gene targeting procedure for Drosophila based on target cleavage by designed zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) (Bibikova et al. 2002, 2003; Beumer et al. 2006). Because the DNA-binding domain consists of Cys2His2 zinc fingers, these hybrid proteins are very flexible in their recognition capabilities. Each finger makes contact primarily with 3 bp of DNA, and arrays of three to four fingers provide sufficient affinity for in vivo binding. Since two ZFNs are required to cleave any single target, a pair of three-finger proteins provides adequate specificity, in principle, to attack a unique genomic sequence.

When a double-strand break (DSB) is created at a specific site in the genome, DNA sequence changes result either from HR with a marked donor DNA or from inaccurate nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). In this study we set out to determine which cellular activities support each of these processes and to learn whether the repair outcome could be biased by elimination of one or another pathway.

Earlier studies showed that Drosophila uses DSB repair mechanisms that are very similar to other eukaryotic organisms (Wyman and Kanaar 2006). In the realm of HR, homologs of the Rad51 (spnA) and Rad54 (okr) proteins are required for the break-initiated meiotic recombination events needed for proper chromosome segregation in females (Kooistra et al. 1997, 1999; Ghabrial et al. 1998; Staeva-Vieira et al. 2003). Mutations in both these genes sensitize somatic cells in early developmental stages to ionizing radiation (IR) and to other DNA damaging agents. In yeast, mutations in the RAD51 gene sensitize cells to IR and lead to severe sporulation defects (Symington 2002). Mutations in RAD54 also confer sensitivity to DNA damaging agents, but are less severely affected in meiosis. In mice absence of the Rad51 protein is lethal in early embryonic development (Lim and Hasty 1996; Tsuzuki et al. 1996). Absence of Rad54 is tolerable, but confers sensitivity to IR and other agents (Essers et al. 1997).

The Drosophila genome encodes components of the major NHEJ pathway, including DNA ligase IV (lig4), Xrcc4, and the Ku proteins (ku70, ku80). Loss of Lig4 sensitizes early developmental stages to ionizing radiation, and this effect is more severe in the absence of Rad54 (Gorski et al. 2003). In other assays a considerable amount of end joining still occurs in lig4 mutants (McVey et al. 2004c; Romeijn et al. 2005), suggesting a secondary or backup pathway, as has been observed in other organisms (Nussenzweig and Nussenzweig 2007). Yeasts rely more heavily on HR for DSB repair, so lig4 mutations have little effect unless HR is impaired. In contrast, lig4−/− mice die early in embryogenesis (Barnes et al. 1998), although they can be rescued by elimination of p53 (Frank et al. 2000).

The molecular process of DSB repair by HR has been studied in Drosophila by introducing a single break at a unique target either by P-element excision or by I-SceI cleavage. The evidence strongly points to an invasion and copying mechanism called synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) (see below) (Kurkulos et al. 1994; Nassif et al. 1994; McVey et al. 2004a). These events are largely dependent on spnA (McVey et al. 2004a; Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007), okr (Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007), and other factors, including mus309 (the Drosophila Bloom syndrome protein, DmBlm) (Adams et al. 2003; McVey et al. 2004b, 2007; Johnson-Schlitz and Engels 2006). When the break site is surrounded by direct repeats, repair proceeds efficiently by single-strand annealing (SSA) (Rong and Golic 2003; Preston et al. 2006).

The key difference between SDSA and SSA is the mechanistic requirement for strand invasion in the former. SSA has rather modest genetic dependencies and is independent of Rad51 and Rad54, but requires that all participating molecules have ends (Symington 2002; Wyman and Kanaar 2006; Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007). In yeast, SSA is reduced in rad52 mutants, but Drosophila has no identified homolog of this gene.

In this study we examined the effects of null mutations in the spnA (Rad51), okr (Rad54), and lig4 genes on ZFN-induced targeting of the Drosophila rosy (ry) locus (Beumer et al. 2006). To reveal the role of SSA, we also compared linear and circular presentation of the donor DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks and crosses:

The DNA repair mutations used in these studies and their sources are given in Table 1. Flies carrying the heat-shock-driven FLP and I-SceI transgenes, P{ry+ 70FLP} and P{w+ 70I-SceI}, were obtained initially from Kent Golic (University of Utah) and are the same as used previously (Bibikova et al. 2003; Beumer et al. 2006). The construction and insertion of the ZFNs for the ry gene, P{ry+ ryA} and P{ry+ ryB}, and the ry donor DNA, P{w+ ryM}, were described earlier (Beumer et al. 2006). The particular ZFN combinations used here are {ryAB2} and {ryAB3}, where the transgenes are inserted on the second and third chromosomes, respectively. The {ryM} donor carries two in-frame stop codons and an XbaI restriction site in place of the ZFN recognition sequences; it confers a null phenotype when incorporated at the ry locus.

Repair mutations

Gene . | Allele . | Mutation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| spnA (Rad51) | spnA057 | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) |

| spnA093A | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) | |

| okr (Rad54) | okrAA | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) |

| okrAG | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) | |

| mei-W68 (Spo11) | mei-W681 | Null | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) |

| mei-W68k05603 | Hypomorph | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) | |

| lig4 | lig4169 | Null | McVey et al. (2004c) |

Gene . | Allele . | Mutation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| spnA (Rad51) | spnA057 | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) |

| spnA093A | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) | |

| okr (Rad54) | okrAA | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) |

| okrAG | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) | |

| mei-W68 (Spo11) | mei-W681 | Null | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) |

| mei-W68k05603 | Hypomorph | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) | |

| lig4 | lig4169 | Null | McVey et al. (2004c) |

Sources: spnA057, Yikang Rong (National Institutes of Health); spnA093A and lig4169, Jeff Sekelsky (University of North Carolina); okr stocks, Trudi Schupback (Princeton University); mei-W68 stocks, Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

Repair mutations

Gene . | Allele . | Mutation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| spnA (Rad51) | spnA057 | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) |

| spnA093A | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) | |

| okr (Rad54) | okrAA | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) |

| okrAG | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) | |

| mei-W68 (Spo11) | mei-W681 | Null | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) |

| mei-W68k05603 | Hypomorph | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) | |

| lig4 | lig4169 | Null | McVey et al. (2004c) |

Gene . | Allele . | Mutation . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| spnA (Rad51) | spnA057 | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) |

| spnA093A | Null | Staeva-Vieira et al. (2003) | |

| okr (Rad54) | okrAA | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) |

| okrAG | Null | Ghabrial et al. (1998) | |

| mei-W68 (Spo11) | mei-W681 | Null | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) |

| mei-W68k05603 | Hypomorph | McKim and Hayashi-Hagihara (1998) | |

| lig4 | lig4169 | Null | McVey et al. (2004c) |

Sources: spnA057, Yikang Rong (National Institutes of Health); spnA093A and lig4169, Jeff Sekelsky (University of North Carolina); okr stocks, Trudi Schupback (Princeton University); mei-W68 stocks, Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

Bringing all the necessary components together for ZFN-induced gene targeting in various genetic backgrounds required a considerable amount of strain construction. This was done using standard techniques and relevant balancer chromosomes (for further description, see FlyBase, http://flybase.org). The presence of each element was confirmed during construction with PCR-based assays, often accompanied by DNA sequencing. Details of the constructions and the primers used for verification are available upon request.

The final crosses that gave progeny that were subjected to ZFN induction were as follows. The numbers correspond to final genotypes listed in Table 2.

Effects of repair mutations on ZFN-induced targeting

Genotype . | . | Donora . | Parentsb . | % yieldersc . | Progenyd . | % rye . | ry/parentf . | HR/tot (% HR)g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. In the male germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 67 | 87 | 4,042 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 12/110 10.9) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 131 | 82 | 7,856 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 25/174 (14.4) |

| 4 | spnA057/093A | L | 123 | 86 | 9,264 | 15.0 | 11.3 | 2/109 (1.8) |

| 5 | spnA093A/093A | L | 44 | 73 | 3,800 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 3/86 (3.5) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 133 | 68 | 8,409 | 13.0 | 8.2 | 11/178 (6.2) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 139 | 78 | 8,749 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5/149 (3.4) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 84 | 2,998 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 2/44 (4.5) |

| 10 | spnA093A/093A | C | 82 | 69.5 | 5,684 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 0/132 (0) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 67 | 85 | 4,088 | 11.5 | 7.0 | 0/131 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 49 | 88 | 3,301 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 23/145 (15.9) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 60 | 77 | 4,774 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 29/95 (30.5) |

| 14 | okrAA/AG | L | 78 | 80 | 5,771 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 7/95 (7.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 15 | lig4169 | L | 134 | 63 | 8,718 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 123/268 (45.9) |

| 16 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | L | 30 | 60 | 1,595 | 13.7 | 7.3 | 9/110 (8.2) |

| 4–6h | spnA−/− | L | 300 | 76 | 21,473 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 16/373 (4.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 17 | lig4169 | C | 93 | 60 | 5,747 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 22/80 (27.5) |

| 18 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | C | 61 | 59 | 4,554 | 11.0 | 8.2 | 0/263 (0) |

| 10, 11i | spnA−/− | C | 149 | 76.5 | 9,772 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 0/263 (0) |

| B. In the female germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 80 | 87.5 | 7,597 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 16/87 (18.4) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 160 | 93 | 17,023 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 56/214 (26.2) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 59 | 41 | 1,115 | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1/80 (1.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 155 | 96 | 13,165 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 16/161 (9.9) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 89 | 4,385 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 4/38 (9.5) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 39 | 51 | 882 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 0/101 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 74 | 82 | 7,360 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 65/165 (39.4) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 92 | 84 | 7,400 | 13.2 | 10.6 | 27/86 (31.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 19 | lig4169/+ | L | 95 | 87 | 9,308 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 32/81 (39.5) |

| 20 | lig4169/169 | L | 62 | 68 | 6,072 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 76/87 (87.4) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 21 | lig4169/169 | C | 77 | 65 | 6,205 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 45/90 (50.0) |

Genotype . | . | Donora . | Parentsb . | % yieldersc . | Progenyd . | % rye . | ry/parentf . | HR/tot (% HR)g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. In the male germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 67 | 87 | 4,042 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 12/110 10.9) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 131 | 82 | 7,856 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 25/174 (14.4) |

| 4 | spnA057/093A | L | 123 | 86 | 9,264 | 15.0 | 11.3 | 2/109 (1.8) |

| 5 | spnA093A/093A | L | 44 | 73 | 3,800 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 3/86 (3.5) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 133 | 68 | 8,409 | 13.0 | 8.2 | 11/178 (6.2) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 139 | 78 | 8,749 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5/149 (3.4) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 84 | 2,998 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 2/44 (4.5) |

| 10 | spnA093A/093A | C | 82 | 69.5 | 5,684 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 0/132 (0) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 67 | 85 | 4,088 | 11.5 | 7.0 | 0/131 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 49 | 88 | 3,301 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 23/145 (15.9) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 60 | 77 | 4,774 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 29/95 (30.5) |

| 14 | okrAA/AG | L | 78 | 80 | 5,771 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 7/95 (7.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 15 | lig4169 | L | 134 | 63 | 8,718 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 123/268 (45.9) |

| 16 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | L | 30 | 60 | 1,595 | 13.7 | 7.3 | 9/110 (8.2) |

| 4–6h | spnA−/− | L | 300 | 76 | 21,473 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 16/373 (4.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 17 | lig4169 | C | 93 | 60 | 5,747 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 22/80 (27.5) |

| 18 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | C | 61 | 59 | 4,554 | 11.0 | 8.2 | 0/263 (0) |

| 10, 11i | spnA−/− | C | 149 | 76.5 | 9,772 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 0/263 (0) |

| B. In the female germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 80 | 87.5 | 7,597 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 16/87 (18.4) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 160 | 93 | 17,023 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 56/214 (26.2) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 59 | 41 | 1,115 | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1/80 (1.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 155 | 96 | 13,165 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 16/161 (9.9) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 89 | 4,385 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 4/38 (9.5) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 39 | 51 | 882 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 0/101 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 74 | 82 | 7,360 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 65/165 (39.4) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 92 | 84 | 7,400 | 13.2 | 10.6 | 27/86 (31.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 19 | lig4169/+ | L | 95 | 87 | 9,308 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 32/81 (39.5) |

| 20 | lig4169/169 | L | 62 | 68 | 6,072 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 76/87 (87.4) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 21 | lig4169/169 | C | 77 | 65 | 6,205 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 45/90 (50.0) |

The donor DNA was provided in linear (L) or circular (C) form.

Number of heat-shocked parents whose progeny were scored.

Percentage of those parents that gave at least one ry offspring.

Total number of offspring scored.

Percentage of all offspring that were ry mutants.

Average number of ry mutants per parent.

Number of HR products over total analyzed, and HR as a percentage of total.

Collected data for all spnA−/− combinations with linear donor: genotypes 4, 5, 6. For comparison with lig4− spnA−/−.

Collected data for all spnA−/− combinations with circular donor: genotypes 10 and 11. For comparison with lig4− spnA−/−.

Effects of repair mutations on ZFN-induced targeting

Genotype . | . | Donora . | Parentsb . | % yieldersc . | Progenyd . | % rye . | ry/parentf . | HR/tot (% HR)g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. In the male germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 67 | 87 | 4,042 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 12/110 10.9) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 131 | 82 | 7,856 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 25/174 (14.4) |

| 4 | spnA057/093A | L | 123 | 86 | 9,264 | 15.0 | 11.3 | 2/109 (1.8) |

| 5 | spnA093A/093A | L | 44 | 73 | 3,800 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 3/86 (3.5) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 133 | 68 | 8,409 | 13.0 | 8.2 | 11/178 (6.2) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 139 | 78 | 8,749 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5/149 (3.4) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 84 | 2,998 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 2/44 (4.5) |

| 10 | spnA093A/093A | C | 82 | 69.5 | 5,684 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 0/132 (0) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 67 | 85 | 4,088 | 11.5 | 7.0 | 0/131 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 49 | 88 | 3,301 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 23/145 (15.9) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 60 | 77 | 4,774 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 29/95 (30.5) |

| 14 | okrAA/AG | L | 78 | 80 | 5,771 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 7/95 (7.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 15 | lig4169 | L | 134 | 63 | 8,718 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 123/268 (45.9) |

| 16 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | L | 30 | 60 | 1,595 | 13.7 | 7.3 | 9/110 (8.2) |

| 4–6h | spnA−/− | L | 300 | 76 | 21,473 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 16/373 (4.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 17 | lig4169 | C | 93 | 60 | 5,747 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 22/80 (27.5) |

| 18 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | C | 61 | 59 | 4,554 | 11.0 | 8.2 | 0/263 (0) |

| 10, 11i | spnA−/− | C | 149 | 76.5 | 9,772 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 0/263 (0) |

| B. In the female germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 80 | 87.5 | 7,597 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 16/87 (18.4) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 160 | 93 | 17,023 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 56/214 (26.2) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 59 | 41 | 1,115 | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1/80 (1.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 155 | 96 | 13,165 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 16/161 (9.9) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 89 | 4,385 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 4/38 (9.5) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 39 | 51 | 882 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 0/101 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 74 | 82 | 7,360 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 65/165 (39.4) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 92 | 84 | 7,400 | 13.2 | 10.6 | 27/86 (31.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 19 | lig4169/+ | L | 95 | 87 | 9,308 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 32/81 (39.5) |

| 20 | lig4169/169 | L | 62 | 68 | 6,072 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 76/87 (87.4) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 21 | lig4169/169 | C | 77 | 65 | 6,205 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 45/90 (50.0) |

Genotype . | . | Donora . | Parentsb . | % yieldersc . | Progenyd . | % rye . | ry/parentf . | HR/tot (% HR)g . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. In the male germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 67 | 87 | 4,042 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 12/110 10.9) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 131 | 82 | 7,856 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 25/174 (14.4) |

| 4 | spnA057/093A | L | 123 | 86 | 9,264 | 15.0 | 11.3 | 2/109 (1.8) |

| 5 | spnA093A/093A | L | 44 | 73 | 3,800 | 12.2 | 10.5 | 3/86 (3.5) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 133 | 68 | 8,409 | 13.0 | 8.2 | 11/178 (6.2) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 139 | 78 | 8,749 | 7.8 | 4.9 | 5/149 (3.4) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 84 | 2,998 | 9.6 | 6.4 | 2/44 (4.5) |

| 10 | spnA093A/093A | C | 82 | 69.5 | 5,684 | 8.4 | 5.8 | 0/132 (0) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 67 | 85 | 4,088 | 11.5 | 7.0 | 0/131 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 49 | 88 | 3,301 | 7.3 | 4.9 | 23/145 (15.9) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 60 | 77 | 4,774 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 29/95 (30.5) |

| 14 | okrAA/AG | L | 78 | 80 | 5,771 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 7/95 (7.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 95 | 88 | 5,761 | 11.0 | 6.6 | 37/209 (17.7) |

| 15 | lig4169 | L | 134 | 63 | 8,718 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 123/268 (45.9) |

| 16 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | L | 30 | 60 | 1,595 | 13.7 | 7.3 | 9/110 (8.2) |

| 4–6h | spnA−/− | L | 300 | 76 | 21,473 | 13.7 | 9.8 | 16/373 (4.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 35 | 91 | 2,191 | 14.0 | 8.7 | 11/88 (12.5) |

| 17 | lig4169 | C | 93 | 60 | 5,747 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 22/80 (27.5) |

| 18 | lig4169 spnA057/093A | C | 61 | 59 | 4,554 | 11.0 | 8.2 | 0/263 (0) |

| 10, 11i | spnA−/− | C | 149 | 76.5 | 9,772 | 9.7 | 6.4 | 0/263 (0) |

| B. In the female germline | ||||||||

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 2 | spnA057/+ | L | 80 | 87.5 | 7,597 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 16/87 (18.4) |

| 3 | spnA093A/+ | L | 160 | 93 | 17,023 | 16.2 | 17.2 | 56/214 (26.2) |

| 6 | spnA057/093A mei-W681/k05603 | L | 59 | 41 | 1,115 | 10.7 | 2.0 | 1/80 (1.3) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 8 | spnA093A/+ | C | 155 | 96 | 13,165 | 16.0 | 13.6 | 16/161 (9.9) |

| 9 | spnA093A/+ mei-W681/+ | C | 45 | 89 | 4,385 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 4/38 (9.5) |

| 11 | spnA093A/093A mei-W681/1 | C | 39 | 51 | 882 | 12.1 | 2.7 | 0/101 (0) |

| 12 | wt | L | 74 | 82 | 7,360 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 65/165 (39.4) |

| 13 | okrAA/+ | L | 92 | 84 | 7,400 | 13.2 | 10.6 | 27/86 (31.4) |

| 1 | wt | L | 110 | 84.5 | 11,853 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 70/269 (26.0) |

| 19 | lig4169/+ | L | 95 | 87 | 9,308 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 32/81 (39.5) |

| 20 | lig4169/169 | L | 62 | 68 | 6,072 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 76/87 (87.4) |

| 7 | wt | C | 43 | 88 | 3,611 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 18/89 (20.2) |

| 21 | lig4169/169 | C | 77 | 65 | 6,205 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 45/90 (50.0) |

The donor DNA was provided in linear (L) or circular (C) form.

Number of heat-shocked parents whose progeny were scored.

Percentage of those parents that gave at least one ry offspring.

Total number of offspring scored.

Percentage of all offspring that were ry mutants.

Average number of ry mutants per parent.

Number of HR products over total analyzed, and HR as a percentage of total.

Collected data for all spnA−/− combinations with linear donor: genotypes 4, 5, 6. For comparison with lig4− spnA−/−.

Collected data for all spnA−/− combinations with circular donor: genotypes 10 and 11. For comparison with lig4− spnA−/−.

1. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; +/MKRS × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}

2. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA057/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6

3. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6 and {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6 × {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO

4. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA057/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6

5. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6

6. mei-W68k05603 {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA057/TM6 × mei-W681 {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6

7, 8. {70FLP}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6

8, 10. {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/+ × {70FLP}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6

9. mei-W681 {70FLP}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6 × {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6

11. mei-W681 {70FLP}/CyO; spnA093A/TM6 × mei-W681 {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6

12. {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; {ryAB3}/TM2 × {ryM}/TM3 Sb

13, 14. okrAG cn/CyO cn; {ryM}/TM6 × okrAA {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; {ryAB3}/TM6

15, 20. w+ lig4169; {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6 × w+ lig4169; {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; +/MKRS

15, 19. w+ lig4169; {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6 × {70FLP} {70I-SceI}CyO; +/MKRS

16. w+ lig4169; {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6 × w+ lig4169; {70FLP} {70I-SceI}/CyO; spnA057/TM6

17, 21. w+ lig4169; {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM}/TM6 × w+ lig4169; {70FLP}/CyO; +/MKRS

18. w+ lig4169; {ryAB2}/CyO; {ryM} spnA093A/TM6 × w+ lig4169; {70FLP}/CyO; spnA057/TM6.

Gene targeting protocol:

The basic procedure was essentially as described earlier (Beumer et al. 2006). Parents of the required genotype were crossed, and their progeny were subjected to a 1-hr 37° heat shock 3 days later. Eclosing adults were screened for the desired phenotypes, often absence of markers on balancer chromosomes, and then were crossed to v; ry506 partners to reveal new germline ry mutations. Individual mutants were subjected to molecular analysis of the ry locus by DNA extraction, PCR, and XbaI digestion (Beumer et al. 2006). One of the PCR primers corresponds to sequences beyond the region of homology present in the donor and thus would amplify only sequences at the target. Many NHEJ (XbaI-resistant) products were sequenced.

Statistical analysis:

Comparisons of the proportion of parents yielding mutants and the proportion of mutants due to HR were performed with a two-tailed Fisher's exact test. Because the number of new mutants as a proportion of total progeny varied widely among parents in each category, a more complex analysis was necessary. Pairwise comparisons were performed using the glm function in the R statistical software package (version 2.8.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna). A quasi-binomial generalized linear model was chosen to model the overdispersion in the data. Ken Boucher of the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah performed this analysis.

RESULTS

Experimental procedure:

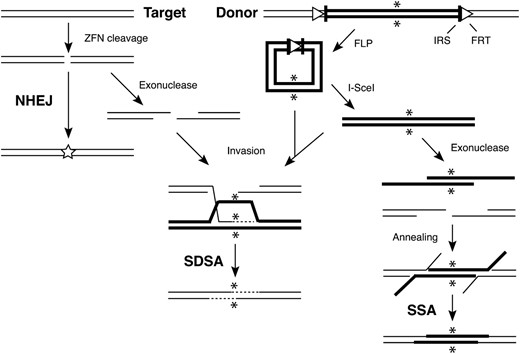

Our gene targeting procedure and mechanistic routes to potential outcomes are illustrated in Figure 1. Coding sequences for two ZFNs, FLP and I-SceI, were inserted in the genome on P elements, each under the control of an hsp70 promoter. Donor DNA was also present as a transgene; sequences homologous to the target were surrounded by recognition sites for FLP (FRT) and I-SceI (IRS in Figure 1). When flies are heat-shocked as larvae, induction of the ZFNs leads to cleavage of the target, while FLP excises the donor as an extrachromosomal circle. I-SceI, when present, makes the donor linear in an ends-out configuration relative to the target DSB.

Molecular mechanisms of gene targeting after a ZFN-induced DSB in the target. The target locus is shown on the left with thin lines illustrating the DNA strands. The donor strands are shown as thick lines on the right, flanked by recognition sites for FLP (FRT, open triangles) and I-SceI (IRS, vertical bars): asterisks indicate the mutant sequence in the donor. ZFN action cleaves the target, which can be repaired directly by NHEJ (left); the star indicates mutations that may arise by inaccurate joining. Target ends can also be processed by 5′ → 3′ exonuclease activity. The donor is excised as a circle by FLP-mediated recombination between the two FRTs. If I-SceI is also present, it makes the donor linear in an ends-out configuration relative to the target. Invasion of the excised donor by one 3′ end of the resected target (center) is followed by priming of DNA synthesis (dashed line). Arrows from both circular and linear donors are intended to indicate that either configuration can serve as a substrate for invasion and synthesis. Withdrawal of the extended strand, annealing with the other resected target end, additional DNA synthesis, and ligation complete the SDSA process, resulting in donor sequences copied into the target. The SSA mechanism is illustrated on the right. Both donor and target ends are resected to reveal complementary single-stranded sequences that anneal. Removal of redundant sequences, possibly some DNA synthesis, and ligation restore the integrity of the target with inclusion of donor sequences.

The break in the target can be repaired directly by NHEJ, often leading to a mutation at the break site. If the target ends are resected by 5′–3′ exonuclease action, repair can proceed by SDSA (Figure 1). One 3′ end invades the donor and primes synthesis using a donor strand as template; the extended strand withdraws and anneals with the complementary strand from the other resected target end; additional synthesis and ligation complete the process. Strand invasion during SDSA depends on the activity of the Rad51 (spnA) protein, and the Rad54 (okr) protein may help with invasion, allow extension of the 3′ end, and/or help with release of the extended strand (Heyer et al. 2006). In contrast, SSA involves no strand invasion and is independent of Rad51 and Rad54. It requires resection of both donor and target ends deeply enough to expose complementary single strands, which then anneal. While SDSA can proceed with either a linear or a circular donor, SSA requires a linear molecule that can be resected.

In the case of a circular donor, it is possible that the invasion intermediate shown for SDSA could be processed in a fashion that leads to integration of the donor at the target, resulting in a partial duplication. Evidence to date, however, suggests that the copying and withdrawal process illustrated in Figure 1 is the predominant form of HR in DSB repair in Drosophila (Kurkulos et al. 1994; Nassif et al. 1994; McVey et al. 2004a).

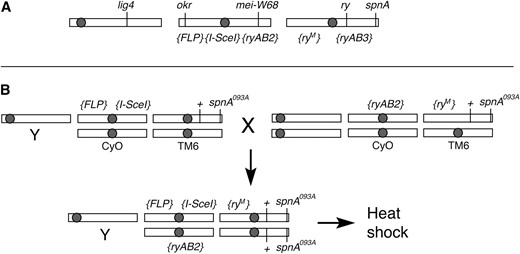

The target in all experiments reported here was the rosy (ry) gene. The ZFN pair, ryA and ryB, was combined with the ryM donor, which has 4.16 kb of homology to the target. The genomic locations of all genes and transgenes are shown in Figure 2A. The FLP and I-SceI transgenes were on chromosome 2, and donor DNA was on chromosome 3. For experiments with spnA and lig4 mutants, a pair of ZFN transgenes on chromosome 2, {ryAB2}, was used. For experiments with okr mutants the ZFNs were on chromosome 3. The ZFN sequences were identical in the two cases, but their separate contexts could influence their expression. {ryM} was kept separate from FLP and I-SceI until the final cross to prevent premature disruption of the donor. The particular cross that generated spnA−/− and spnA+/− flies is illustrated in Figure 2B.

Schematic illustration of genetic procedures for gene targeting at ry. (A) Locations of genes and transgenes. Open bars represent D. melanogaster chromosomes: X, left; 2, middle; and 3, right. Shaded circles represent centromeres. The locations of endogenous genes are as follows: lig4, X, 12B2; okr, 2L, 23C4; mei-W68, 2R, 56D9; ry, 3R, 87D9; and spnA, 3R, 99D3. The transgenes shown below chromosomes 2 and 3 are known to lie on those chromosomes, but their exact locations have not been mapped. {ryAB2} and {ryAB3} are pairs of ZFNs. The mutant ry donor is {ryM}. (B) Illustration of the cross to produce flies with the gene targeting materials in an spnA−/− background. The Y chromosome is shown simply as Y. + indicates the wild-type ry gene. Typically crosses were done in both directions with each set of components coming from males or females. CyO and TM6 are balancers for chromosomes 2 and 3, respectively. Flies with the desired genotype and their siblings were heat-shocked as larvae and then identified as adults on the basis of the absence of markers on the balancers. New ry mutants were revealed by crossing those adults to a known ry deletion mutant.

Adults were removed and a 37° heat shock was applied to the progeny 3 days after initiation of the cross that brought all the components together. When adults eclosed, they were examined for the appropriate phenotype and then crossed individually to flies carrying the ry506 deletion to reveal new germline ry mutants. Many of these were characterized by molecular analysis, which distinguishes HR products that received a diagnostic XbaI site from the donor from NHEJ products that are resistant to XbaI. Many of the NHEJ products were sequenced to confirm their identification and to reveal the nature of the mutant sequence. We report the following parameters, separately for males (Table 2A) and females (Table 2B): the number of fertile heat-shocked parents, the percentage of these that yielded at least one ry mutant, the total number of offspring, the percentage of offspring that were ry mutants, the average number of mutants per fertile parent, and the percentage of mutants that were products of HR with the donor DNA.

Effect of spnA on gene targeting:

Males homozygous for spnA null mutations are viable and fertile (Staeva-Vieira et al. 2003), apparently because male meiosis is achiasmate—i.e., it does not rely on recombination for proper chromosome segregation (Yoo and McKee 2005). Homozygous females are sterile, but fertility can be rescued by mutations in the mei-W68 gene, the homolog of SPO11, which makes the meiotic DSBs that initiate recombination (Ghabrial and Schupbach 1999).

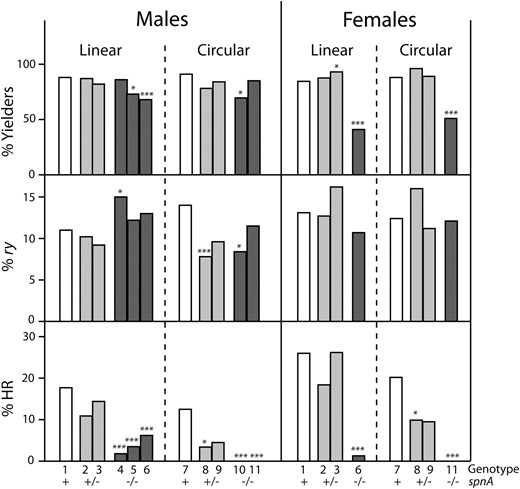

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, targeting at ry was very efficient in wild-type males and females when the donor was linear (genotype 1). Between 84 and 88% of all parents in which ZFN expression was induced gave at least one mutant offspring. New ry mutants comprised 11–12% of all offspring. Approximately 18% of these mutants had the donor sequence at the ry locus as a result of HR, and the remaining 82% had novel NHEJ mutations. These results are very similar to those we reported earlier (Beumer et al. 2006), although overall yields of mutants and of HR products were somewhat lower in the current experiments.

Histograms showing data from spnA experiments. The three tiers show the percentage of heat-shocked parents that yielded at least one ry mutant offspring (% Yielders, top), the percentage of all offspring that were new ry mutants (% ry, middle), and the percentage of analyzed mutants that were products of homologous recombination between target and donor (% HR, bottom). Data are presented separately for male and female parents and for linear and circular donor configurations. Genotypes of the parents are indicated along the x-axis; the numbers correspond to entries in Table 2, and the spnA genotype is shown explicitly. Results of comparisons to the corresponding wild type are indicated: *0.05 > P > 0.005; **0.005 > P > 0.001; ***P < 0.001.

In males, loss of one or both spnA alleles had little effect on the percentage of parents yielding mutants or the percentage of mutant offspring. In heterozygotes (genotypes 2 and 3), the proportion of HR products dropped slightly, but not significantly (P > 0.1; see supporting information, Table S1 for exact P-values). When both spnA alleles were mutant, the proportion due to HR dropped very significantly, from 17.7% in wt to 1.8–6.2% (P < 0.001 for all three cases) (Table 2A, genotypes 4–6; Figure 3). This was true in homozygotes and in compound heterozygotes, as well as in combination with mei-W68 mutations, so we are confident the effect is due to spnA.

In females, mutating one spnA allele had little effect on the yield of mutants or the proportion due to HR (Table 2B, Figure 3). The spnA−/− mei-W68−/− mutants had severely reduced fertility, ∼20 offspring per parent, as opposed to ∼100 in other backgrounds (Table 2B). This resulted in reduced proportions of parents with mutant offspring and number of mutants per parent. As a percentage of total offspring, however, the frequency of induced ry mutants was essentially the same as in wild type. The percentage of HR was very significantly reduced, from 26% in wild type to 1.3% in spnA−/− mei-W68−/− (P = 5 × 10−8). These results indicate that an spnA-dependent process, likely SDSA, is responsible for most of the donor capture in these experiments.

Circular donor—the role of SSA:

Roughly three-fourths of HR products in males and 95% in females seemed to be generated by an spnA-dependent invasion mechanism. The remainder was suspected to be due to SSA. We tested this directly by providing the donor DNA in circular, rather than linear form (see Figure 1). This was accomplished by expressing FLP to excise the donor, but not I-SceI (Bibikova et al. 2003).

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3, the circular donor gave very similar numbers in wild-type flies (genotype 7) as were seen with the linear donor (genotype 1). The modest reduction in percentage of HR in both sexes was statistically insignificant (Table S1). spnA heterozygotes (genotype 8) showed reduced levels of HR in both males (P = 0.00025) and females (P = 0.062), suggesting that the Rad51 protein may be limiting in amount and that use of a circular donor may be more demanding than use of a linear one. In the absence of spnA, no HR products were recovered among >100 analyzed. This was true in both males and females (P = 3 × 10−5 in males; P = 4 × 10−7 in females) and indicates that, as suspected, the residual HR products arose by the end-dependent SSA mechanism.

Effect of okr on gene targeting:

In previous studies, okr mutations showed a similar effect on DSB repair as observed with spnA (Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007). We did not attempt to rescue female sterility of the okr mutants, and heterozygotes produced mutants with parameters indistinguishable from wild type (Table 2B). Because different ZFN transgenes were used for these experiments, independent wild-type controls were performed (Table 2A, genotype 12). In males the rise in percentage of HR products observed in okr+/− heterozygotes (genotype 13) was significant (P = 0.010). In okr−/− homozygotes (genotype 14), the percentage of HR fell, just as seen with spnA, although only marginally in this case (P = 0.071).

The observation that the absence of Rad54 had a more modest effect than absence of Rad51 is consistent with previous observations in Drosophila, yeast, and mice (Essers et al. 1997; Symington 2002; Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007). Presumably this reflects a more accessory role for Rad54, one that can be performed (albeit less efficiently) by other proteins, in contrast to an essential role for Rad51.

Effect of lig4 on gene targeting:

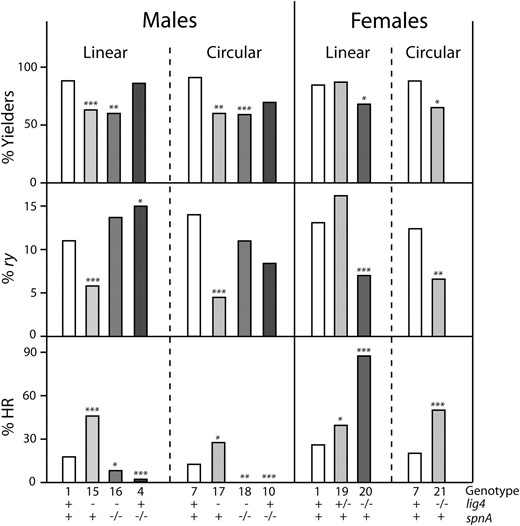

The majority of new mutants generated by ZFN-induced cleavage arose by NHEJ in wild-type flies. We wanted to know whether these were produced by the canonical lig4-dependent pathway. Both mutant males and homozygous mutant females are viable and fertile (McVey et al. 2004c). Because the targeting reagents were the same as those used for the spnA experiments, the same controls (genotypes 1 and 7) apply to experiments with the lig4 mutants.

Loss of lig4 in males led to a reduction in the proportion of parents giving new mutants and in the yield of ry mutants, but to an increase in the proportion due to HR (Table 2A, Figure 4). This was true for both linear (genotype 15) and circular (genotype 17) donors. When spnA was also absent, eliminating SDSA, and the donor was linear (genotype 16), the mutant yield was restored to the wild-type level. The percentage of HR dropped significantly (P = 0.028), but not to a level as low as with spnA−/− alone. This suggests that SSA may compete more effectively with alternative NHEJ than with the canonical lig4-dependent mechanism. When the donor was circular in lig4 spnA double mutants (genotype 18), no HR products were recovered, just as with spnA−/− alone. The total yield of mutants was equal to that in wild type, despite the inability to perform SDSA, SSA, or canonical NHEJ. This indicates that alternative NHEJ can be quite efficient.

Histograms showing data from lig4 experiments. Data are presented as in Figure 3. Both the lig4 and spnA genotypes are shown explicitly at the bottom. Combined lig4 and spnA mutations were analyzed only in males, and results for spnA−/− only are included for comparison.

In females with a linear donor, loss of one lig4 allele (Table 2B and Figure 4, genotype 19) led to recovery of an increased proportion of HR products relative to wild type. In the complete lig4 knockout (genotype 20), the overall yield of mutants dropped somewhat, but the percentage of HR products was even higher: 87%, compared to 26% in wild type. The same effects were observed in lig4−/− flies with a circular donor (genotype 21): the yield of mutants fell, but the percentage of HR was significantly higher.

The results from both males and females indicate that HR is favored in the absence of lig4. When spnA is also absent, a robust alternative NHEJ process generates mutations at the break site without a significant loss in fecundity.

Nature of the NHEJ mutations:

In other systems it has often been observed that end-join mutants formed in the absence of DNA ligase IV are structurally different from those formed in its presence. In particular, microhomologies are more commonly found at repair junctions recovered from lig4 mutants (Verkaik et al. 2002; Romeijn et al. 2005; Liang et al. 2008). We examined 62 independent NHEJ mutations from lig4 mutants and 112 NHEJ mutations from lig4+ backgrounds in this study. We also compared these with 120 NHEJ products identified from lig4+ flies in previous studies (Beumer et al. 2006).

Broadly speaking, the mutations in lig4− and lig4+ backgrounds were quite similar, but there were some differences (see Figure S1 and Figure S2). In both situations we recovered small insertions and deletions, in approximately equal numbers, centered on the ZFN cleavage site. Single-base-pair deletions were more common in lig4+ (22% of all NHEJ mutations) than in lig4− (5%). A unique 9-bp deletion was found frequently in lig4− (16%), but rarely in lig4+ (3%). This deletion shows a 1-bp microhomology at the junction, but overall the presence of microhomologies was not significantly higher in lig4− products. Simple insertions (without accompanying deletions) were much more common in lig4+ (35% vs. 8%). The particular 4-bp insertion that represents fill-in of the 5′ overlap generated by ZFN cleavage and blunt-end joining was more common in lig4+ (19%) than in lig4− (3%).

An RNA-templated insertion?

Most of the insertions recovered in NHEJ products were small (<15 bp), but occasionally we saw quite long insertions, and these could be traced to their genomic source. In lig4+ flies a 200-bp insertion was largely from the 18S rRNA gene, and a 399-bp insertion matched sequences from the histone gene cluster, except for short stretches at the insert ends. One 64-bp insertion from a lig4− parent came from sequences downstream of the ry gene, but was joined back at the ZFN target, replacing 71 bp that were deleted. In all these cases it seems likely that a copy–join mechanism was at play (Merrihew et al. 1996). We envision that one end at the target DSB was resected and the 3′ end used as a primer to copy from a template elsewhere in the genome. After some synthesis, the end withdrew and rejoined with the other end from the original break. This process is similar to SDSA, but it seems unlikely that invasion mediated by extensive homology was involved, since no such homology was evident. Indeed, the examples noted here all came from spnA−/− parents.

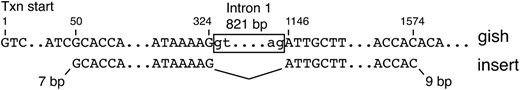

A unique 720-bp insertion recovered from a lig4− spnA−/− male was particularly interesting. As shown in Figure 5, this sequence could be traced to the Drosophila melanogaster gilgamesh (gish) gene, which lies on chromosome 3R (89B9–12) ∼3.25 Mb from ry. Remarkably, the insert has a precise exon–exon junction, cleanly lacking intron 1 of the major gish mRNAs. No pseudogene with this structure has been identified in the D. melanogaster sequence. Furthermore, there is only a single mismatch in the 5′-UTR between the insert and the deposited genome sequence, strongly suggesting that the template for the insert derives from the active gish locus. This all indicates that a spliced mRNA or partially spliced mRNA precursor provided the template for the insert sequence.

Illustration of the relationship between the D. melanogaster gish gene (top) and the insert found in one NHEJ product (bottom). Positions in the gene are numbered from the transcription start. Corresponding sequences in the insert begin at position 50 and extend to position 1574, except that intron 1 (positions 325–1145) is cleanly missing. In addition, there are 7 bp on the upstream end and 9 bp on the downstream end of the insert that do not match either the gish gene or the ry target.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows how ZFN-induced DSBs are repaired in Drosophila during targeted mutagenesis and gene replacement. The dominant mode of HR depends on the activities of the Rad51 and Rad54 proteins. Such a dependence is characteristic of invasion-based mechanisms; in Drosophila this is likely SDSA (Kurkulos et al. 1994; Nassif et al. 1994; McVey et al. 2004a). In the absence of Rad51, residual HR between target and donor appears to proceed by SSA, as HR is completely eliminated by providing only a circular donor. The primary mode of NHEJ depends on DNA ligase IV; in its absence the proportion of HR products rises significantly. Surprisingly, a high level of NHEJ mutagenesis is maintained in the absence of both Rad51 and Lig4, indicating that a secondary inaccurate pathway functions in these circumstances.

In comparing our results with previous studies of DSB repair in Drosophila, one must keep in mind the admonition that, in experiments of this sort, the answer one gets depends on how one phrases the question. That is, the relative involvement of various pathways will depend on the nature of the substrates that are offered. Two extensive recent studies employed substrates in which an I-SceI-induced break was flanked by direct repeats (Johnson-Schlitz et al. 2007; Wei and Rong 2007). Not surprisingly, SSA was the predominant mode of repair, and this was independent of Rad51 and Rad54. In our ZFN-mediated gene targeting protocol, completion of repair by SSA alone would be somewhat more demanding. Two independent incidences of resection and annealing are needed, one at each end of the donor and of the target (Figure 1). In addition, the sequences to be annealed do not start out in proximity, although how this might affect the process is not entirely clear.

It is remarkable in our gene targeting protocol that the donor DNA is used so efficiently to repair ZFN-induced breaks. In every case there is only a single copy of the integrated donor in each diploid cell, yet a sizeable proportion of new mutants result from HR between donor and target. This is particularly true in the absence of DNA ligase IV, where HR products represent about half of all mutations in males and nearly 90% in females. Clearly liberation of the donor DNA from its chromosomal site with FLP facilitates its association with the homologous target. Both in the presence (Bibikova et al. 2003) and in the absence (Rong and Golic 2000) of a break in the target, making the donor extrachromosomal and linear stimulates HR by at least an order of magnitude.

Our results with lig4 mutants generally show larger changes than those observed in previous studies. McVey et al. (2004c) saw very little effect of lig4− on repair after P-element excision, either in wild-type or in spnA−/− backgrounds. Both the timing and the nature of the induced DSBs were different from our experiments: P transposase was constitutively expressed, presumably from shortly after fertilization, and P excision left 17-nucleotide single-stranded 3′ tails and a 14-kb gap for repair. We do not know how these features would influence lig4-dependent end joining. Both Johnson-Schlitz et al. (2007) and Wei and Rong (2007) saw decreases in NHEJ in lig4 mutants. Not surprisingly, given the nature of their substrates, they observed a compensatory increase in SSA products. The latter group found, as did we, that mutagenic NHEJ was reduced, but not eliminated. Both these studies used breaks made by I-SceI, which leaves 4-nucleotide 3′ tails. ZFN cleavage produces 4-nucleotide 5′ tails (Smith et al. 2000). The effect of tail length and polarity on repair outcomes has not been studied systematically.

Choice of repair pathway:

In most of the cases we have studied, the yield of new mutants, measured as percentage of all offspring, was not greatly affected by manipulation of the repair pathways, even though the distribution of NHEJ and HR products varied over a wide range. This suggests that pathways compensate for each other to ensure effective repair. Proving this conclusion is quite difficult, since both the HR and major NHEJ processes generate products that are invisible in our analysis, in addition to the new mutants we score. Repair by spnA-dependent HR using the homologous chromosome or sister chromatid as a template would restore ry+. The same is true of accurate direct ligation of the ZFN-produced ends, which could be mediated by lig4. Thus, when Rad51 or Ligase IV is absent, not only is one route to new mutations disabled, but also some wild-type products will not be produced. We cannot determine whether broken chromosomes that would have been repaired by HR were simply lost or whether they were redirected to repair by NHEJ. We do not know the absolute frequency of ZFN-induced breaks or what the effect might be on fecundity of losing some germline cells at early stages of development.

In the case of lig4 mutants, the yield of sequence alterations in the ry target decreased significantly to about half the wild-type value. The proportion of HR-derived mutants increased in these flies, which might suggest that the breaks destined for inaccurate NHEJ were simply lost. The data indicate, however, that the numbers of HR mutants increased, not just the proportion; and some of the breaks not repaired by NHEJ may have been repaired back to ry+ via HR, as suggested above. When both lig4 and spnA were missing, and even when the circular donor prevented SSA, the yield of mutants was indistinguishable from that in wild type. An alternative inaccurate NHEJ process is clearly operating in those circumstances, and it may be that accurate repair to restore ry+ is no longer possible, resulting in an apparent preservation of mutant yield.

NHEJ mutations:

Many studies have reported that, as in mammalian cells, NHEJ in Drosophila produces insertions as well as deletions at the DSB site (Takasu-Ishikawa et al. 1992; Kurkulos et al. 1994; Staveley et al. 1995; McVey et al. 2004c; Min et al. 2004; Romeijn et al. 2005), and that has been our experience (Bibikova et al. 2002; Beumer et al. 2006; and this study). Perhaps surprisingly, we saw only modest effects of lig4 mutation on the nature of the NHEJ products. In other systems lig4-independent end joining makes greater use of microhomologies at the junction (Verkaik et al. 2002; Pan-Hammarstrom et al. 2005; Morton et al. 2006; Liang et al. 2008; McVey and Lee 2008), but that was not the case here. Since the genetic requirements for this backup system are not known, we cannot speculate on how it might be affected by the design of our experiments or the developmental timing of repair. A recent study found an increase in large deletions in the absence of lig4 in Drosophila (Wei and Rong 2007), and this was true of lig4-deficient human and yeast cells as well (Wilson et al. 1997; So et al. 2004). Our PCR-based assay might have missed some of these, but PCR failures were rare, and use of primers flanking the break site at greater distance did not reveal such products.

The most surprising single NHEJ product we recovered was the insertion that was clearly derived ultimately from spliced gish RNA. We cannot determine whether RNA was the direct template for repair or whether a fortuitous reverse transcript was available for the process. Previous studies have found copies of RNA inserted at DSB sites in yeast, but as these RNAs were derived from retrotransposons, their insertion was attributed to copying from the corresponding cDNAs (Moore and Haber 1996; Teng et al. 1996). A recent study showed that synthetic RNAs can be used in yeast as templates to repair DSBs by HR, albeit at considerably lower frequency than synthetic DNAs (Storici et al. 2007). A plant mitochondrial gene that migrated to the nuclear genome during evolution appears to have proceeded via an RNA intermediate, as the nuclear copy reflects changes introduced by RNA editing (Nugent and Palmer 1991).

The presence of apparently untemplated nucleotides at many junctions, including those between the gish and ry sequences (Figure 5), suggests template-independent DNA synthesis during NHEJ repair in both the lig4-dependent and lig4-independent processes. Similar observations have been made in many other systems (Roth et al. 1989; Gorbunova and Levy 1997). Interestingly, the multifunctional bacterial NHEJ protein, LigD, contains a polymerase domain that is capable of template-independent nucleotide addition (Pitcher et al. 2007), and some eukaryotic DNA polymerases also possess this activity (Nick McElhinny et al. 2005).

Conclusion:

Gene targeting stimulated by ZFN-induced cleavage proceeds by well-defined mechanisms. Most homologous gene replacement by recombination with a donor DNA occurs by SDSA, with a minor fraction by SSA. The major NHEJ pathway depends on DNA ligase IV, although a robust backup pathway completes repair in the absence of other alternatives. When lig4 is mutated, a substantially increased proportion of repair events proceed by HR, leading to donor incorporation in a large fraction of cases. We have recently simplified our procedure by delivering ZFNs and donor DNA to flies through direct embryo injection (Beumer et al. 2008). Making use of the results of the current study, we found that injection into lig4 mutant embryos led to a large increase in HR repair, without overall loss of efficiency.

Footnotes

Present address: Boston Biomedical Research Institute, 64 Grove St., Watertown, MA 02472.

Supporting information is available online at http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/genetics.109.101329/DC1.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: S. E. Bickel

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Yikang Rong, Jeff Sekelsky, Trudi Schupbach, and the Drosophila Stock Center for providing mutant stocks and advice on their husbandry; to John Wilson for his comments on the manuscript, and to Ken Boucher for the complex statistical analysis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health awards GM58504 and GM78571 (to D.C.) and in part by a University of Utah Cancer Center support grant.

References

Adams, M. D., M. McVey and J. J. Sekelsky,

Barnes, D. E., G. Stamp, I. Rosewell, A. Denzel and T. Lindahl,

Beumer, K., G. Bhattacharyya, M. Bibikova, J. K. Trautman and D. Carroll,

Beumer, K. J., J. K. Trautman, A. Bozas, J.-L. Liu, J. Rutter et al.,

Bibikova, M., M. Golic, K. G. Golic and D. Carroll,

Bibikova, M., K. Beumer, J. K. Trautman and D. Carroll,

Essers, J., R. W. Hendriks, S. M. Swagemakers, C. Troelstra, J. de Wit et al.,

Frank, K. M., N. E. Sharpless, Y. Gao, J. M. Sekiguchi, D. O. Ferguson et al.,

Ghabrial, A., and T. Schupbach,

Ghabrial, A., R. P. Ray and T. Schupbach,

Gorbunova, V., and A. A. Levy,

Gorski, M. M., J. C. J. Eeken, A. W. M. de Jong, I. Klink, M. Loos et al.,

Heyer, W. D., X. Li, M. Rolfsmeier and X.-P. Zhang,

Johnson-Schlitz, D. M., and W. R. Engels,

Johnson-Schlitz, D. M., C. Flores and W. R. Engels,

Kooistra, R., K. Vreeken, J. B. M. Zonneveld, A. de Jong, J. C. J. Eeken et al.,

Kooistra, R., A. Pastink, J. B. M. Zonneveld, P. H. M. Lohman and J. C. J. Eeken,

Kurkulos, M., J. M. Weinberg, D. Roy and S. M. Mount,

Liang, L., L. Deng, S. C. Nguyen, X. Zhao, C. D. Maulion et al.,

Lim, D. S., and P. Hasty,

McKim K. S., and A. Hayashi-Hagihara,

McVey, M., and S. E. Lee,

McVey, M., M. Adams, E. Staeva-Vieira and J. J. Sekelsky,

McVey, M., J. R. LaRocque, M. D. Adams and J. J. Sekelsky,

McVey, M., D. Radut and J. J. Sekelsky,

McVey, M., S. L. Andersen, Y. Broze and J. Sekelsky,

Merrihew, R. V., K. Marburger, S. L. Pennington, D. B. Roth and J. H. Wilson,

Min, B., B. T. Weinert and D. C. Rio,

Moore, J. K., and J. E. Haber,

Morton, J., M. W. Davis, E. M. Jorgensen and D. Carroll,

Nassif, N. A., J. Penney, S. Pal, W. R. Engels and G. B. Gloor,

Nick McElhinny, S. A., J. M. Havener, M. Garcia-Diaz, R. Juarez, K. Bebenek et al.,

Nugent, J. M., and J. D. Palmer,

Nussenzweig, A., and M. C. Nussenzweig,

Pan-Hammarstrom, Q., A. M. Jones, A. Lahdesmaki, W. Zhou, R. A. Gatti et al.,

Pitcher, R. S., N. C. Brissett and A. J. Doherty,

Preston, C. R., C. C. Flores and W. R. Engels,

Romeijn, R. J., M. M. Gorski, M. A. van Schie, J. N. Noordermeer, L. H. Mullenders et al.,

Rong, Y. S., and K. G. Golic,

Rong, Y. S., and K. G. Golic,

Roth, D. B., X. B. Chang and J. H. Wilson,

Smith, J., M. Bibikova, F. G. Whitby, A. R. Reddy, S. Chandrasegaran et al.,

So, S., N. Adachi, M. R. Lieber and H. Koyama,

Staeva-Vieira, E., S. Yoo and R. Lehmann,

Staveley, B. E., T. R. Heslip, R. B. Hodgetts and J. B. Bell,

Storici, F., K. Bebenek, T. A. Kunkel, D. A. Gordenin and M. A. Resnick,

Symington, L. S.,

Takasu-Ishikawa, E., M. Yoshihara and Y. Hotta,

Teng, S. C., B. Kim and A. Gabriel,

Tsuzuki, T., Y. Fujii, K. Sakumi, Y. Tominaga, K. Nakao et al.,

Verkaik, N. S., R. E. Esveldt-van Lange, D. van Heemst, H. T. Bruggenwirth, J. H. Hoeijmakers et al.,

Wei, D. S., and Y. S. Rong,

Wilson, T. E., U. Grawunder and M. R. Lieber,

Wyman, C., and R. Kanaar,

Yoo, S., and B. D. McKee,