-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Norman H Horowitz, T. H. Morgan at Caltech: A Reminiscence, Genetics, Volume 149, Issue 4, 1 August 1998, Pages 1629–1632, https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/149.4.1629

Close - Share Icon Share

AT the urging of Professor G. M. McKinley, who taught genetics at the University of Pittsburgh, I applied for graduate school at Caltech, was accepted, and arrived in Pasadena for the opening of the fall term of 1936. It would never have occurred to me to go to a school so far away—3 days by train, in distant California—had it not been for Dr. McKinley, but this was only the first of a series of lucky choices that formed my career.

On arriving at the Caltech campus and locating the Kerckhoff Laboratory of Biology—a building so grand in my eyes that I felt the need to ask a passing student if this was indeed the home of the biology department—I entered and found the office of the Chairman, Thomas Hunt Morgan, on the second floor. I identified myself to Morgan's fearful secretary, Miss Brusstar, and was ushered into Morgan's office. I recognized him immediately from photographs published in 1933, when he won the Nobel Prize. My first encounter with this man who was to have a large influence on my life was brief. I stood in front of his desk, and Morgan looked up at me from a stack of papers in front of him. “Horowitz,” he said, “you are going to work with Albert Tyler.” He then directed me to Tyler's office. I had never heard of Albert Tyler, but at the moment I was not inclined to ask questions of Morgan, and I went off dutifully to find Albert Tyler's office.

I soon learned that Tyler was an embryologist—what today would be called a developmental biologist. He worked on the early development of sea urchins and other marine invertebrates. He had been Morgan's student at Columbia University and had come to Pasadena with the Morgan group in 1928, when the Biology Division at Caltech was founded. I soon learned that Morgan had long since given up working with Drosophila and had returned to an earlier love, marine animals. Drosophila genetics had become too complex for him. Morgan was a discoverer, not a bookkeeper, and after the basic findings of Drosophila genetics had been made, he left the subject in the competent hands of his students Sturtevant, Bridges, and Muller (and Mrs. Morgan) and moved on to other fields. When I came to know him, he was working on a genetic problem in the primitive marine chordate, Ciona. On most weekends, Morgan and Tyler went to the Kerckhoff Marine Laboratory at Corona del Mar, California, a little over an hour's drive from Pasadena. Being Tyler's graduate student, I would now accompany them.

As an undergraduate, I had done some research on transplantation in salamanders that had resulted in an article in the Journal of Experimental Zoology, and this, combined with the fact that I had indicated no preferred field of graduate study in my application, had no doubt determined Morgan's decision to send me to work with Tyler. These events now afforded me the opportunity to become more than casually acquainted with Morgan.

The three of us would leave Pasadena at about nine o'clock on Saturday morning in Tyler's Model-A Ford, with Tyler at the wheel, Morgan in the front passenger seat, and me in the back. We proceeded to the Newport Beach Yacht Club, a few miles up the coast from Corona del Mar. The pilings there were the home of a large population of Morgan's experimental animal, Ciona, an ascidian. We would pull a sufficient number of them off the pilings and take them with us, in a bucket of seawater, to the marine station.

Ciona is hermaphroditic, but self-sterile. The rule is that the sperm of a given individual do not fertilize the eggs of the same individual, but are fertile with the eggs of all other Ciona. Occasional exceptions are found. Morgan perceived here a genetic problem and set himself the task of learning what he could about it. At the marine laboratory, he would set up several experiments, each consisting of a square array of Syracuse dishes containing seawater, 5 to 10 dishes on a side, in which the sperm and eggs from 5to 10 individuals were crossed in all possible combinations. In some experiments, acid—which suppressed self-sterility—was added to some of the dishes. Morgan examined each dish under the microscope and noted the result. He did not, as I remember, have a notebook for recording his data, but pulled envelopes and pieces of paper out of his pockets for this purpose. (He must at some point have put his data into more durable form, since he published many papers containing the numerical results of these experiments.) Tyler and I did our own work in the same large laboratory room as Morgan. One of Tyler's roles was to keep an eye on Morgan's experiments. I suspect that he contributed more than a little to saving Morgan's data from chaos.

Morgan worked on Ciona until his death in 1945. He was a tireless experimenter. His last paper appeared in the Journal of Experimental Zoology the month he died. He did not solve the problem of self-sterility in Ciona, but he approached a solution. In a paper published in 1944, he summarized his results. From experiments with offspring of selfed animals that he reared in the laboratory, he concluded that at least three—and more likely five—genes, with an indefinitely large number of alleles, were involved.

Morgan's passion for experimentation was symptomatic of his general scepticism and his distaste for speculation. He believed only what could be proven. He was said to be an atheist, and I have always believed that he was. Everything I knew about him—his scepticism, his honesty—was consistent with disbelief in the supernatural.

One of my favorite memories of Morgan is that of a visit he was paid one day by the well-known British author, H. G. Wells. Wells, I had read in the papers, was in Southern California for a reason I have long since forgotten. A few days later, I happened to see him on the sidewalk outside the Kerckhoff Lab, heading for the main entrance. I was immediately struck by his spiffy appearance: the perfect vision of an Englishman abroad, he was wearing a white suite, Panama hat, spats, and a cane. Morgan, who was evidently expecting him, greeted him at the door. In contrast to Wells' elegance, Morgan was his usual unpressed, unstylish self. I got the impression that the two were acquainted and that this was a social call. They moved into the building, and Morgan took Wells on a tour. One could tell where in the course of the tour they were located, because Morgan, who was hard of hearing, assumed that anyone his own age (they were both born in 1866) suffered from the same affliction, and he spoke in a loud voice. Eventually, they went to Morgan's office, and I lost track. It was clear that these two aging gentlemen, so different in appearance, were in fact deeply similar. Both were revolutionaries in their way, and they were united in their passion for biology and in their nonconformist, rationalistic approach to the world.

Morgan was known for his sardonic wit. A famous example were the words he spoke in a speech in 1909 at a meeting of the American Breeders Association (ABA). He had not yet gotten into genetics, and he was critical of it. He said: “In the modern interpretation of Mendelism, facts are being transformed into factors at a rapid rate. If one factor will not explain the facts, then two are invoked; if two prove insufficient, three will sometimes work out … .” A year later, he discovered the white-eyed mutation in Drosophila that led, eventually, to the modern chromosomal theory of heredity. I first heard his words to the ABA quoted by the professor (it may have been Ernest Anderson) in a graduate genetics course at Caltech. They served to remind us scientists-to-be that a real scientist changes course when he is forced to do so by evidence. It is instructive to compare the words of Morgan spoken in 1909 to the ABA with those referred to above written in 1944 in summarizing his Ciona results.

Morgan made fun of human gullibility. His attitude was displayed weekly at the General Biology Seminar, held Tuesday evenings at 7:30 in a room in the Kerckhoff Laboratory. The Morgans lived then in a comfortable ranch house on the north side of Kerckhoff, across San Pasqual Street, which traversed the campus. Both the house and the street are gone now. The Morgans would cross the street to Kerckhoff after dinner, carrying with them the New York Times that they received daily. The paper came from the East by train, so it was a week old by the time it arrived in Pasadena. Morgan would open the seminar by reading and commenting on stories with a scientific aspect, many of them exhibiting the folly of humankind, and these he treated in his wittiest style. Everyone was amused, except perhaps Calvin Bridges, who was the kindest of men and not easily moved to laugh at the foolishness of others. I recall that among the regular attendees at the seminar were two elderly sisters, both retired school teachers. One had taught biology in high school, and she invariably had one or two uninteresting questions for the speaker of the evening. When she spoke up at the end of the lecture, an almost audible sigh would go up from the audience. Only Bridges, when he was the speaker, could be counted on to reply to her politely and at length. For him, everyone was educable.

Morgan would finally introduce the speaker and then sit down in the front row next to Mrs. Morgan. He was usually asleep by the time the speaker had spoken two sentences. Mrs. Morgan would nudge him and whisper “Tom! Tom!” After a brief nap, he awakened refreshed and frequently had an acute question for the speaker at the end.

I attended these seminars for three years, but I now can remember only the beginning of one of them. That was the lecture Max Delbrück gave shortly after his arrival in 1937 as a Rockefeller Foundation Fellow from Germany. Here was a bright theoretical physicist from the leading European centers of quantum physics, come to Caltech to learn about the wonders and mysteries of

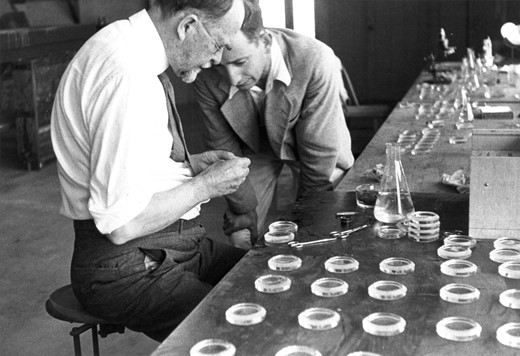

Morgan and Tyler (and Syracuse dishes) at the Kerckhoff Marine Laboratory in 1931 (Courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of Technology).

genetics. He began his talk by drawing a circle on the blackboard and saying, “Let us imagine the cell is a homogeneous sphere.” The whole room burst into laughter. Except, perhaps, Bridges.

I am sometimes asked what I know about Morgan's reputed anti-Semitism. I know that there is documentary evidence for anti-Semitic statements by Morgan, but in the years I knew him, I never encountered, or even suspected, any such prejudice on his part. On the contrary, as far as I could see he treated everyone fairly. The fact that he grew up in Kentucky in the 19th century would perhaps incline one to expect some prejudice from him, but if he grew up with prejudices, he had outgrown them by the time I came to know him. I never experienced or even heard of them until after his death. Morgan was a complicated man, and I can easily believe that there were sides of his character that I never saw, but I am certain that during the years I knew him, anti-Semitism was not one of them.

My last memorable encounter with him occurred at the time of my Ph.D. Oral Examination, in 1939. Normally, Albert Tyler would have been chairman of the examining committee, since I had done my thesis with him, but I was informed a day or two before the exam that Morgan would be in charge. I was also told that the Dean of the Graduate School, Richard C. Tolman, would be present. Tolman, a well-known physical chemist, had not yet attended a biology Ph.D. exam and had decided to come to mine, which was scheduled to be the first one held in biology that year. I believe that Morgan's presence as chairman was related to the fact that Tolman would be there. It was his way of welcoming the Dean to the Biology Division. The exam went smoothly. Morgan went through the committee inviting questions, holding Tolman and himself for last. I can now remember only these two last questions. Tolman took the theme of his questions from the title of my thesis, which dealt with the rate of respiration of marine eggs. He asked me to derive the equations for first- and second-order chemical reactions. I had no trouble with the first-order law, but I flubbed the integration step of the second-order equation. (Today, I doubt if I could derive either of them.) Tolman accepted my answer, however, saying that “for a biologist” I had done pretty well.

Finally it was Morgan's turn. Every graduate student knew that Morgan always asked questions about the anatomy and physiology of the experimental animal used by the candidate. To prepare for that I had spent my lunch hour reading Hegner's College Zoology. True to form, Morgan asked me to describe the respiratory system of the sea urchin. I did so perfectly. To my surprise, Morgan said, “No, Horowitz, you have described the starfish.” I knew that he was wrong, but the exam was going well, and I didn't want to embarrass him over a triviality, so I kept quiet.

The exam ended, and I was passed. A couple of days later, I ran into Morgan in the hall. He called to me and said he had found that I had been right in the exam. He apologized, and I thanked him. I do not remember ever seeing him again. Not long afterward, newly married, I left with my wife for Stanford University, where I was to work in the laboratory of Morgan's son-in-law, Douglas Whitaker. I had been awarded a National Research Council Fellowship, one of the few postdoctoral fellowships that were available before the war, and one that I have always believed Morgan's influence helped me obtain. Normally, a recipient of that fellowship would have gone to Europe, but war was imminent, and we went to Stanford instead.

The most important thing that happened to me at Stanford was finally to meet George Beadle. Beadle had been on the Caltech faculty when I submitted my application to Caltech in early 1936. Then he left for Paris, where he worked with Boris Ephrussi. After that he moved to Harvard and then Stanford. He told me later that he had voted for my admission as a graduate student because of my undergraduate transplantation paper. He said he had been doing transplantation studies himself, in Drosophila—obviously a bond between us! The meeting with Beadle eventually changed my life, but that is another story.

Footnotes

This essay commemorates the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Division of Biology at Caltech by Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1928.